Fresh accusations that the Assad regime has used chemical weapons in the ongoing civil war have led many to renew calls for the world to take stronger actions to stop the growing humanitarian crisis.

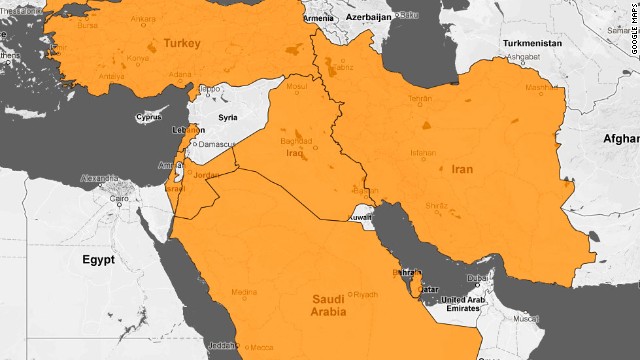

yria regiona

yria regiona

But recent polls have shown Americans are very reluctant to support military interventions in Syria. In a Huffington Post/YouGov poll, as few as 5% of respondents were willing to commit troops to the cause

The Obama administration has been similarly hesitant to get involved in Syria.

Q&A: Is Syrian war escalating to wider conflict?

While the administration has made some efforts to respond to humanitarian crises elsewhere in the world -- the U.S. joined NATO in its successful mission to assist Libyan rebels, military advisers have been sent to Uganda to combat the Lord's Resistance Army and to Jordan to help Syrian rebels -- full-scale military intervention in Syria does not appear to be on the table.

Read more: Opposition source -- Syrian rebels get U.S.-organized training in Jordan

President Obama's varying view on humanitarian intervention is in keeping with over 20 years of inconsistent American policy on the issue.

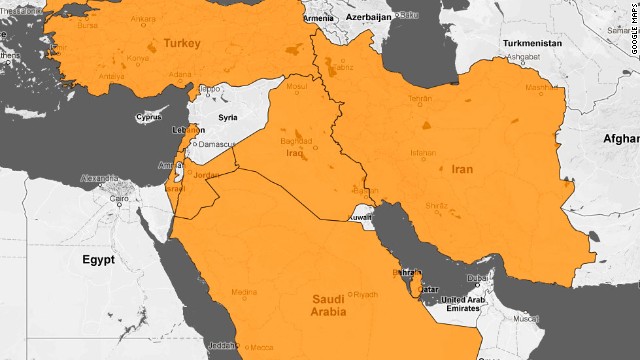

yria regiona

yria regiona

Over the last 20 years, the U.S. government has chosen to intervene in Bosnia, Kosovo, Somalia, Haiti, and Libya while resisting calls to take action in Rwanda and Sudan.

Read more: 5 reasons Syria's war suddenly looks more dangerous

To better predict whether the U.S. will intervene in Syria, or any other similar crisis, we must understand why Washington selectively engages in humanitarian intervention missions.

Our recent research on when and why the U.S. engages in humanitarian intervention emphasizes two factors that might force the U.S. government's hand on humanitarian intervention: public opinion and Congressional partisanship. We analyzed public opinion polls and congressional votes during four episodes of humanitarian intervention -- Somalia, Haiti, Bosnia and Kosovo -- and found, as recent debates seems to suggest, humanitarian intervention is mired in the mundane world of politics. Contrary to conventional wisdom, politics do not end at "water's edge."

There is some good news to report: both the general public and individual legislators understand and are responsive to the moral imperative of stopping humanitarian crises.

The public is generally supportive of humanitarian missions. Even in the recent polls on Syria, respondents believe something should be done, even if they are unsupportive of military action by the U.S..

Further, Congress is not wholly unresponsive to public preferences regarding intervention in humanitarian emergencies. Legislative support is more likely in cases where public opinion generally favors intervention.

Those who push for more humanitarian missions can increase support for such missions by raising public outcry for action.

But the bad news is that humanitarian crises, like in Syria, which should rise above politics as usual, are often mired in that very spot.

Although public opinion appears to have an influence on legislative behavior, traditional factors such as partisanship have the strongest influence on how legislators cast their votes.

Humanitarian intervention is most likely when the U.S. president enjoys a majority in Congress. In the case of the 1990s, humanitarian interventions failed to get off the ground when President Clinton lost majorities in Congress.

If American politics is becoming increasingly partisan, future administrations should have an even harder time galvanizing the domestic support they need to address any humanitarian crises.

Opinion: Obama's no-win options in Syria

This does not mean, however, that humanitarian intervention will only occur when a president enjoys a majority in Congress. As the recently launched humanitarian missions suggest, politicians are learning the lessons of the 1990s and circumventing Congress.

This helps explain why President Obama's decision to contribute the U.S. military to NATO operations in Libya proceeded without Congressional authorization; the president was surely aware that such a vote would go down to defeat in a Republican-controlled House and deeply partisan Senate.

Congress was similarly bypassed in October 2011 when the administration deployed military advisers to Uganda.

Congress was similarly bypassed in 2011 and 2013 when the administration deployed military advisers to Uganda and Jordan, respectively.

For those who advocate for a strong humanitarian intervention in Syria, our research does not paint a completely gloomy picture. Instead, it simply suggests that domestic political will is a necessary precondition for intervention missions and should not be overlooked.

It is important to recognize that partisan bickering and political jockeying shape responses to humanitarian crises just as in trade policy, arms control, and immigration politics. While the atrocities are singular in their importance, the politics of dealing with them are not.

For those eager to craft a uniform and effective international response to humanitarian crises as in Syria, they must first turn their attention to domestic politics.

The political elites who must decide when, whether, where and how to fulfill the responsibility to protect, face their own domestic political battles. Ignoring these contexts threatens to over-simplify both the problems and the promises of humanitarian intervention

No comments:

Post a Comment